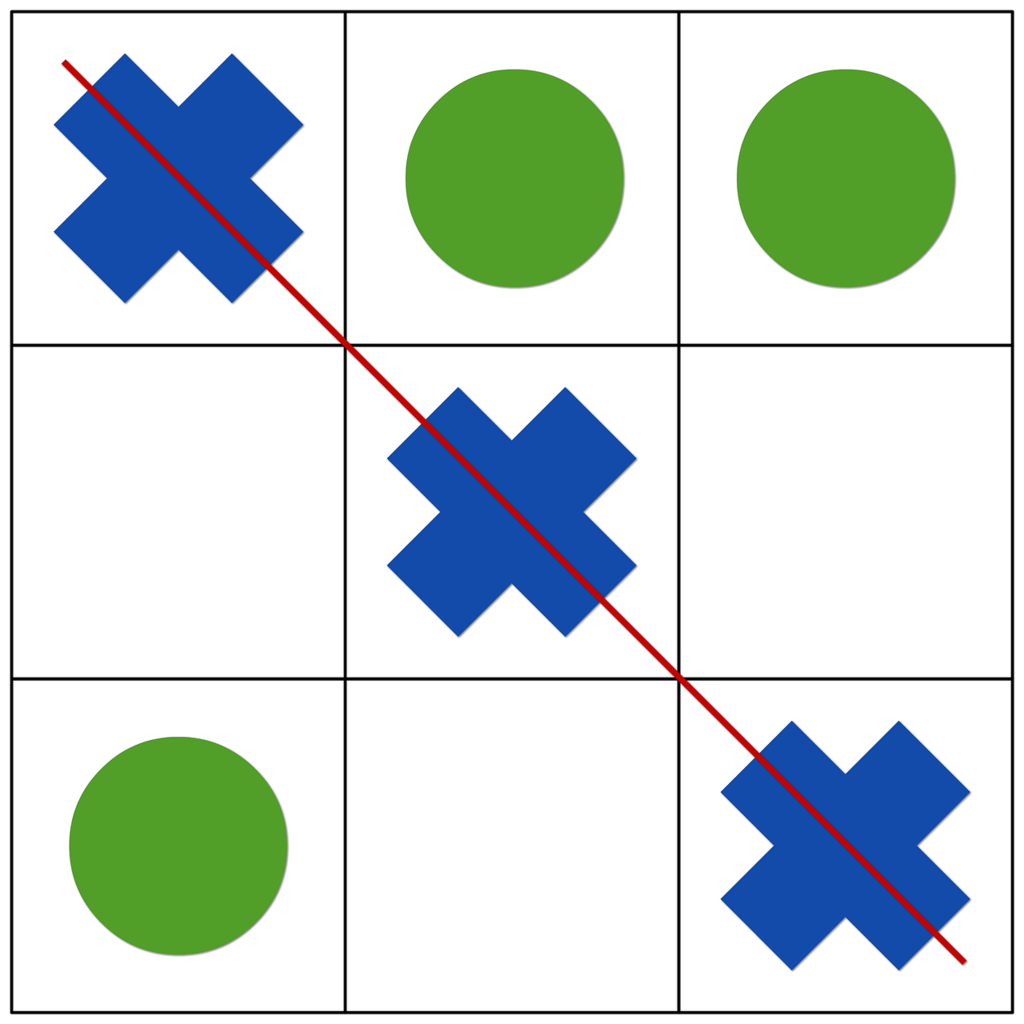

At age 13, Bill Gates wrote his first computer program. It was a simple game of tic-tac-toe that allowed a user to compete against a computer. Beyond its simplicity, this episode was the beginning of Gates’s connection with programming, at a time when access to computers was still much limited.

Gates was at the private Lakeside School in Seattle when he first encountered a computer. The school had acquired access to a Teletype Model 33 terminal, connected by telephone line to a remote General Electric computer.

This equipment had no screen or graphical interface: instructions were entered using a keyboard, and the results were printed on continuous paper.

In that environment, Gates learned to program in BASIC, a high-level language designed to make it easier to teach programming to students. Along with his colleague Paul Allen—who would later co-found Microsoft—he explored the capabilities of the system, which operated in time-sharing, allowing multiple users to access the resources of a single mainframe.

As Gates himself recounted in later interviews, the tic-tac-toe game was written so that a player could compete against the computer, which made decisions using rules programmed by the player.

The program allowed the system to analyze possible plays and respond automatically, a process that, at the time, represented a technical challenge for a teenager without a college education.

Gates and Allen’s interest in the systems’ operation went beyond formal learning. Both began exploring the software’s limitations, to the point of being temporarily suspended from the school’s terminal for detecting and exploiting errors in the time allocation system.

Far from sanctioning them definitively, the company that owned the system—Computer Center Corporation—ended up hiring them as assistants to detect errors and improve the software’s performance.

This period of teenage experimentation is cited by Gates as instrumental in his later decision to found a software development company. In 1975, together with Allen, they created a version of the BASIC language adapted for the Altair 8800 microcomputer. This development marked the beginning of Microsoft, at a time when the software industry had not yet emerged as such.

The tic-tac-toe episode appears as a minor anecdote in Gates’s official biographies, but it illustrates the early relationship between self-directed learning, technical curiosity, and access to emerging technologies. It also shows how, in a context of limited resources, certain school environments facilitated exposure to computing tools that were not widely available.

Today, programming a simple game may seem trivial, but in 1968 it required understanding the basics of computational logic, memory usage, and keyboard input, as well as being able to tolerate slow and unintuitive processes.

Gates, like other pioneers of the digital age, took his first steps without internet access, without online tutorials, or without personal devices. He falls within a generation that began programming through trial and error, using code as the primary language for interacting with machines.

In retrospect, Gates’s first program is less relevant for its outcome than for what it represents: the beginning of what would transform the global technology industry. Although Microsoft didn’t emerge from that game, the logic that made it possible was the starting point for a career based on understanding how to operate and control computer systems.