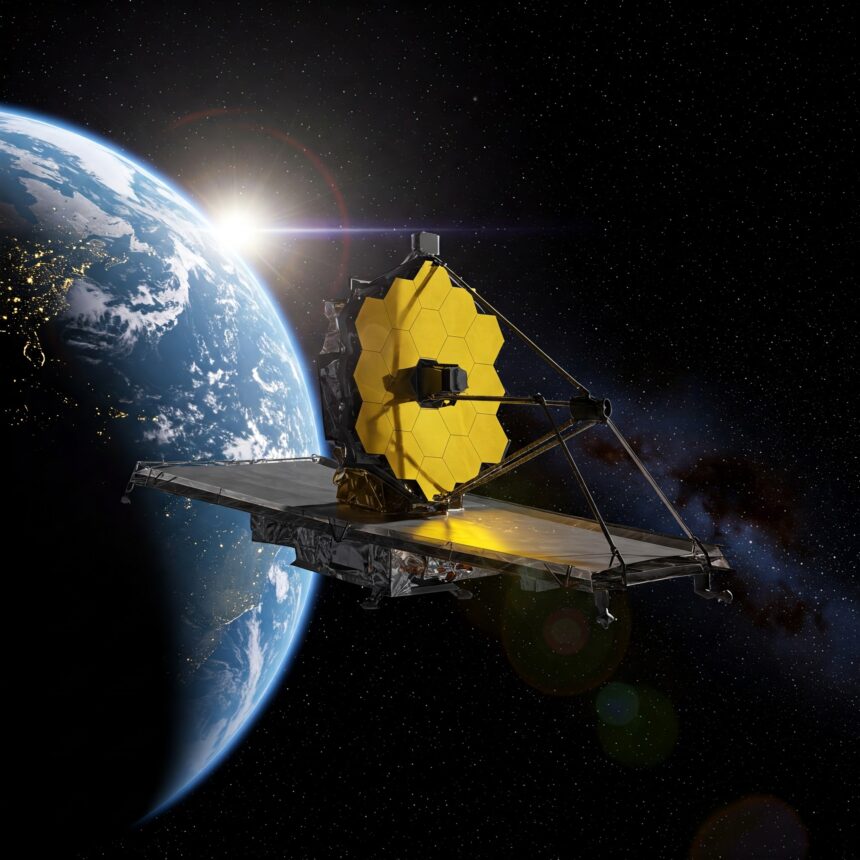

The James Webb Space Telescope has directly observed the presence of carbon dioxide on planets outside our solar system. This is the first time scientists have detected the gas in an exoplanet’s atmosphere; making it all the more astonishing that this feat occurred on not one, but four exoplanets, all belonging to the HR 8799 system, located 130 light-years from Earth.

Observations from the James Webb telescope provide strong evidence that these four giant planets in the HR 8799 system formed in a very similar way to Jupiter and Saturn, through the slow buildup of solid cores. The findings were published in the latest issue of The Astronomical Journal .

“By detecting these strong buildups of carbon dioxide, we’ve shown that there is a sizable fraction of heavier elements, such as carbon, oxygen, and iron, in the atmospheres of these planets,” said William Balmer, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University and lead author of the paper, in a statement.

It is a robotic instrument capable of rotating to any part of the sky in less than 20 seconds, which can track the afterglow of colliding or merging stars.

Although these gas giants aren’t capable of supporting extraterrestrial life, the detection of CO2 offers clues to the mystery of how distant planets form. “Given what we know about the star they orbit, this likely indicates they formed by core accretion, which, for planets we can see directly, is an exciting conclusion,” said Balmer, also the paper’s lead author .

HR 8799 was born 30 million years ago, a young age compared to the 4.6 billion years our solar system has existed. Still hot from their violent formation, the planets of HR 8799 emit large amounts of infrared light. This provides scientists with valuable data on how their formation compares to that of a star or a brown dwarf.

“Our hope with this type of research is to understand our own solar system, life, and ourselves in comparison to other exoplanetary systems, so we can contextualize our existence,” Balmer said. “We want to take pictures of other solar systems and see how they are similar or different from our own. From there, we can try to understand how strange our solar system really is, or how normal it is.”

The James Webb Space Telescope imaged young, giant exoplanets and detected carbon dioxide! The findings suggest that the giant exoplanets in the HR 8799 system likely formed like Jupiter and Saturn. (1/5) pic.twitter.com/HOTNMO0k2X

— Space Telescope Science Institute (@SpaceTelescope) March 17, 2025Carbon dioxide is an essential ingredient for life to have existed on Earth, making it a key target in the search for life elsewhere in outer space. Since CO2 condenses into tiny ice particles in the deep cold of space, its presence can shed light on planetary formation.

Jupiter and Saturn are thought to have formed from a bottom-up process, in which a bunch of tiny icy particles came together to form a solid core, which then absorbed gas to grow into the gas giants we know today.

“We have other lines of evidence pointing to the formation of these four planets in HR 8799 via this upward approach,” said Laurent Pueyo, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute and co-author of the paper. “How common is this for long-period planets that we can image directly? We don’t know yet, but we propose further observations via Webb, inspired by our carbon dioxide diagnostics, to answer this question.”

Unlocking the potential of the James Webb

The James Webb Telescope also deserves praise, as it has demonstrated its ability to do more than infer the atmospheric composition of exoplanets from starlight measurements; in fact, it has demonstrated its ability to directly analyze the chemical composition of atmospheres as distant as these.

The heat signatures of PDS 70 b and PDS 70 c, both growing planets, have emerged using a novel observation method with the James Webb Telescope.

Normally, the Webb telescope can barely detect an exoplanet when it passes in front of its host star, due to the great distance between us. But on this occasion, direct observation was made possible thanks to the James Webb coronagraphs, instruments that block starlight to reveal otherwise hidden worlds.

“It’s like putting your thumb in front of the sun when you look at the sky,” Balmer said. This adjustment, similar to that of a solar eclipse, allowed the team to search for infrared light in wavelengths that reveal specific gases and other atmospheric details.

“These giant planets have very important implications,” Balmer said. “If these enormous planets act like bowling balls zooming through our solar system, they can disrupt, protect, or in some ways do both to planets like our own. Therefore, better understanding their formation is crucial to understanding the formation, survival, and habitability of Earth-like planets in the future.”