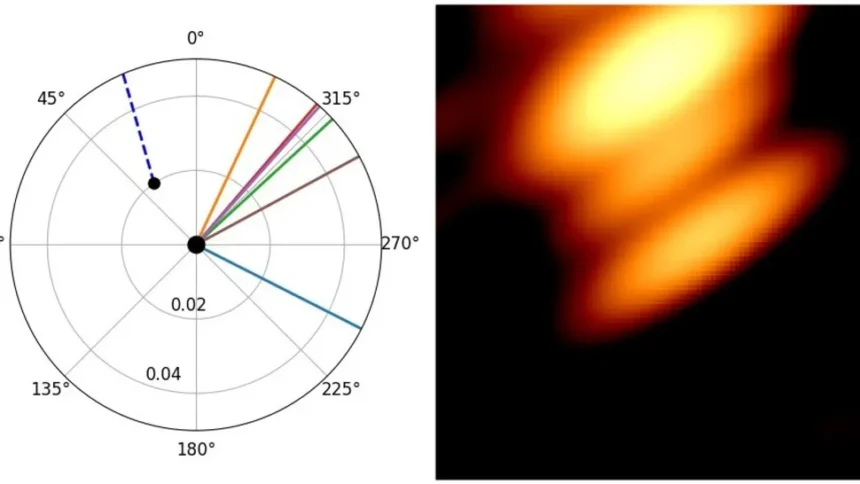

For the first time, an international team managed to capture an image showing two black holes orbiting one another, a result that offers visual proof of a phenomenon previously inferred only via indirect observations. The discovery was made in the core of the quasar OJ287, located about 5 billion light-years from Earth.

The research was led by Mauri Valtonen, an astronomer at the University of Turku (Finland), together with an international consortium, and published in The Astrophysical Journal. The scientists emphasised that this achievement was possible by combining observations made on Earth and in space using a network of radio telescopes.

How the Image Was Obtained and Why It Matters

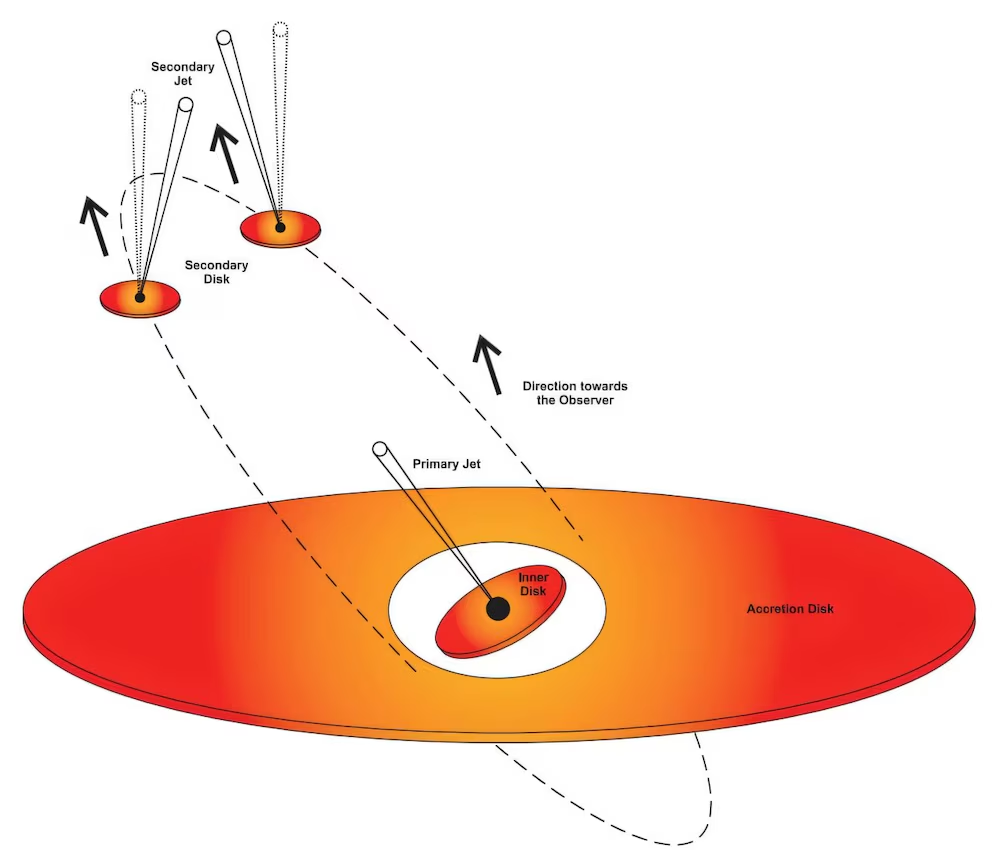

The team employed radio imaging technology, combining data from terrestrial telescopes and the Russian satellite RadioAstron, whose radio telescope extended to nearly half the distance to the Moon. This reach allowed an unprecedented resolution, sufficient to distinguish two separated sources near the intense glow characteristic of quasars.

“In the image, the black holes are identified by the intense particle jets they emit. The black holes themselves are perfectly black, but they can be detected by these particle jets or by the glowing gas surrounding the hole,” explained Valtonen.

OJ287, known for its exceptional luminosity, had long aroused suspicion within the astronomical community due to its pattern of brightness variations at roughly 12-year intervals. For more than forty years, hundreds of astronomers monitored those regular fluctuations, suspecting that they were caused by two black holes in mutual orbit.

The History Behind OJ287 and the Road to Visual Confirmation

The first images of the region now associated with OJ287 date back to the late 19th century, long before the existence of black holes was even considered plausible. The object came under intensive study in the 1980s by researchers at the University of Turku, after astronomer Aimo Sillanpää identified regular variations in brightness and proposed the theory of a binary black hole pair.

Recent advances refined the predicted orbit and estimated physical parameters, but visual confirmation remained elusive. The NASA satellite TESS detected light emissions from both objects, albeit as a single point, insufficient to resolve them individually.

Meanwhile, the newly obtained image of the two orbiting black holes marks a significant milestone, linking a longstanding astrophysical hypothesis to observable evidence. “For four decades we wondered if it would be possible to detect them at the same time. Finally, the proof is in view,” said Valtonen.